Sprained your ACL?

Let us guide you through

Hello everyone and welcome to our July blog. We’re halfway through the year already, which means the soccer season, rugby and netball are in full swing! Added to this the start of the ski season. Why is this relevant you ask? Well these are sports that send quite a lot of people our way. It’s this time of year where we start to see an influx of knee injuries and it’s an especially busy time of year for treating ACL sprains - the injury any keen sports person will want to avoid at all costs! Unfortunately, there has been a significant increase in ACL injuries over the last twenty years, with nearly 200,000 people requiring surgical repair between 2000-2015 in Australia alone.

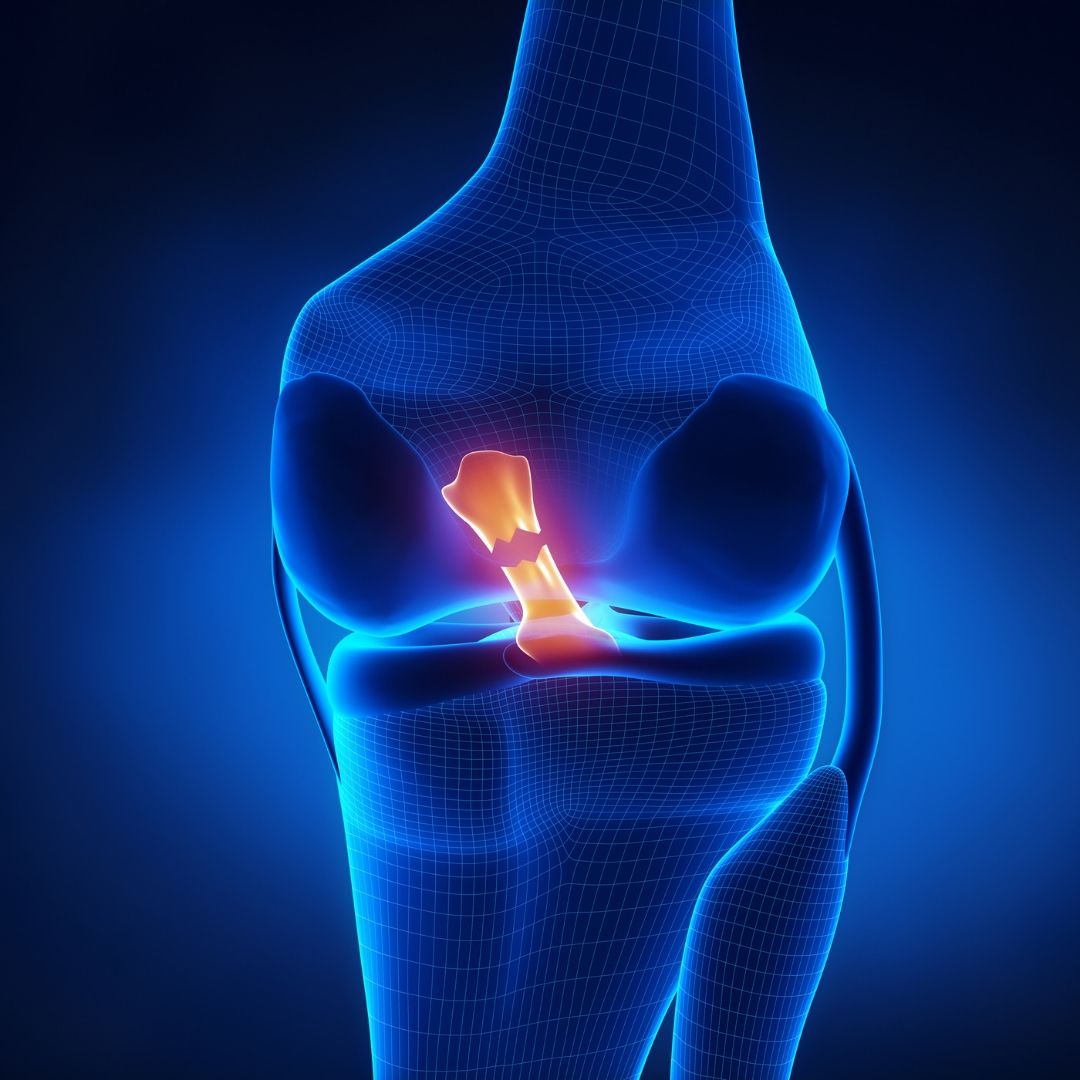

A bit of anatomy for you

The ACL, or Anterior Cruciate Ligament is one of four main ligaments that support and stabilise the knee joint (the others being the posterior cruciate, medial collateral, and lateral collateral lig-aments). Deep inside the knee it connects the thigh bone (femur) to the shin bone (tibia) and its main purpose is to stop the shin bone from moving forward and over-rotating when we perform certain movements. It is particularly important at stabilising the knee during movements such as jumping and landing, pivoting with a quick change in direction, and deceleration (slowing down) movements. It’s no surprise then that the way people tend to injure this ligament is by performing exactly those types of movements. Injury occurs when the ligament gets taken beyond its capa-bilities of supporting and stabilising the knee, and the result is a sprain of the ligament. Imagine a netball player jumping to catch the ball, and then landing and pivoting on one foot to change di-rection quickly. As they turn, their knee twists and falls inwards while the foot is still planted on the ground… And that’s all it takes. Minor sprains involve only part of the ligament, but less fortu-nate occurrences may tear the ligament completely - known as a ‘rupture’.

What to expect when it happens

If you are unfortunate enough to experience such an injury here is a list of signs and symptoms to look out for:

• An audible pop or crack in the knee

• Intense pain (especially in the immediate aftermath of a full rupture)

• Inability to continue activity

• A possible large swelling of the knee (this may be delayed in certain instances)

• A feeling of instability if attempting to perform further movement

• Restricted knee movements with inability to straighten the knee in particular

• Widespread tenderness (especially on the inside and outside of the knee)

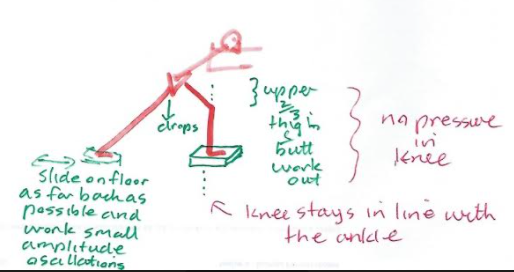

Single joint and whole body movement changes in ACL injured athletes returning to sport (Smeets et al 2020, Med Sc Sp Ex, 52, 8, 1658-1667). The most prominent change is the increased activation of the hamstrings muscles. In surgical cases, this may be due to the use of the hamstrings (semitendinosis) tendon as a donor for the graft. Additionally, this can be a compensatory action to minimise the anterior shear of the tibia under the femur. As such, whole body compensation would be a more erect landing pattern on hopping and jumping. These authors did not find such a pattern, apart from decreased ankle flexion on the side ways hop. Another factor, may simply be that hamstring activation is a means whereby we limp, or it may represent conscious activation from physiotherapeutic reinforcement during exercise rehabilitation.

Reduced knee flexion moments have also been found, which presumably represents a compensatory action to reduce anterior shear. Additionally, increased hip and trunk flexion moments were observed which moves the centre of mass more anteriorly, thereby increasing the loading of the posterior chain whilst sharing the muscular synergistic loading across the upper 2/3 of the thigh (hamstrings and quadriceps) as well gluteal contractions, which invariably lead to pelvic floor and abdominal contractions. These authors found increased trunk and hip flexion angles in 3 of 5 tasks but only in the long hop did they find an anterior centre of mass. As such, they concluded that clinicians use task independent single joint motions in their assessment of return to normal function.

Programs such as FIFA 11 for ACL rupture prevention can also be used as part of the rehabilitation process. Additionally, a Delphi consensus reaching process for return to sport should also be consulted.

- Return to Sport : Delphi consensus RTS ACL

- FIFA 11 Plus :https://www.fifamedicalnetwork.com/lessons/prevention-fifa-11

It’s important to know that ACL injuries will often come with extra baggage. As if tearing a ligament inside the knee isn’t bad enough, unlucky recipients will also often damage the medial col-lateral ligament, the meniscus (a cartilage type structure inside the knee), or the cartilage that covers the end surfaces of the bones. Some refer to an injury which includes the ACL, MCL and meniscus as the ‘unhappy triad’. And you’d be quite unhappy indeed! However, there is light at the end of the tunnel! With the right guidance and professional care, your recovery journey can be a successful one!

So what next?

The first thing you need to do is see a professional. Contact our friendly team at Back in Business Physiotherapy today who can help to diagnose you. The sooner after initial injury the better, be-cause once the swelling kicks in, it’s a bit more difficult to diagnose accurately (at least until the swelling has reduced). Your physio may refer you on for imaging; often an MRI will be performed alongside an x-ray. Once you have a solid diagnosis, the next important choice is whether to treat surgically or conservatively. Generally, if it is a partial tear, a conservative approach would be taken, but this totally depends on the person and what their goal is in life. It’s quite possible to live life with no ACL at all, but you will have to be prepared to adjust what types of physical activities you partake in. A professional football player who is still young and has a career ahead of them may opt for a surgical repair with a subsequent intensive rehabilitation process to stand the best possible chance of performing at a professional level again. It’s a complex decision with many factors to consider, such as age, level of injury and the persons occupation. Your physio will be able to guide you to the right choice for you.

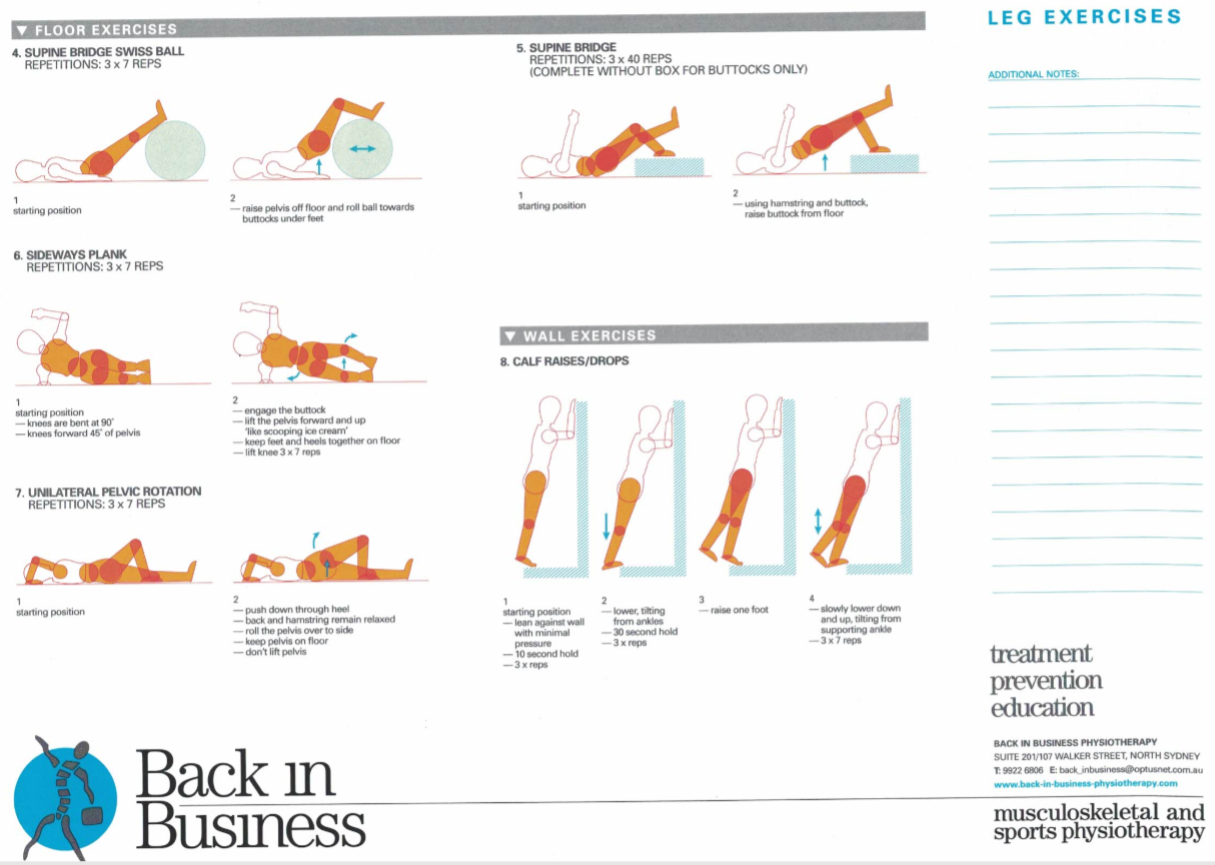

If you opt for surgical repair, then the rehabilitation process generally takes around one year. For a partial tear without surgery, the process would be faster. Ultimately your physio will follow a structured protocol to get you back to fitness again. Phases of rehab will include the following:

• Reduce swelling and restore full range of motion

• Begin to progressively strengthen the lower limb muscles (i.e. quads, hamstrings)

• Move from non to partial to full weight bearing (depending on the injury)

• Improve balance and control of movement

• Begin gross body movements such as squatting and lunging

• Return to jogging, running and pivoting

• Return to sport (training and fun match play)

Increased hamstring activity can lead to increased compressive forces in the knee resulting in the early onset of Osteoarthritis. Similarly, excessive shear can result in OA. Therefore, rehabilitation needs to bear this in mind and find an optimal hamstring loading pattern.

Further variations on the reverse lunge can include diagonal reversal, sideways slides and the use of a step.

60-70% of shock absorption in the knee can come form the calf, so eccentric calf strength is important. As mentioned previously, trunk and hip strength are also important factors in knee control.

As stated before, the recovery process really depends on each person’s individual situation. For you it might be completely different than your neighbour or family member. Keep in mind, that it is possible to re-injure your ACL following surgery, with most cases of re-injury occurring within one year. For many, the risk of injuring the other knee is a distinct possibility, so it is pivot-al (no pun intended) that you follow our advice here at Back in Business Physiotherapy to ensure you achieve your goal and stay clear of injury in the future. Anyone for shooting some hoops? Safely, of course!

ACL rupture and the menstrual cycle

References:

1. Zbrojkiewicz, D. et al. 2018. Increasing rates of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young Australians, 2000–2015. The Medical Journal of Australia. 208 (8). 354-358. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.00974

2. Brukner, P. et al. 2017. Clinical Sports Medicine. 5th ed. Australia: McGraw-Hill Education

Uploaded 10 July 2021